Yesterday, on 17 January 2026, after years of difficult negotiations, a treaty to protect the high seas came into force. This is a historic moment for the marine environment and also for the international community in times of war and the formation of new blocs. What is the story behind it and which are the problems (not yet) solved?

The development of maritime law over commons, territoriality, exploitation rights, and preservation dates back in centuries. The modern concept of the seas as ’common heritage of mankind’ has been formulated only in 1967 by Malta’s UN ambassador Arvid Pardo, inspiring his colleague Elisabeth Mann Borgese [1], daughter of the German novelist Thomas Mann, to found the International Ocean Institute in 1972 and to focus her commitment to ecology and collectivism on the preservation of the seas. Her activities contributed to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), agreed upon in 1982 and entered into force in 1994. [2]

The sea beneath and beyond control

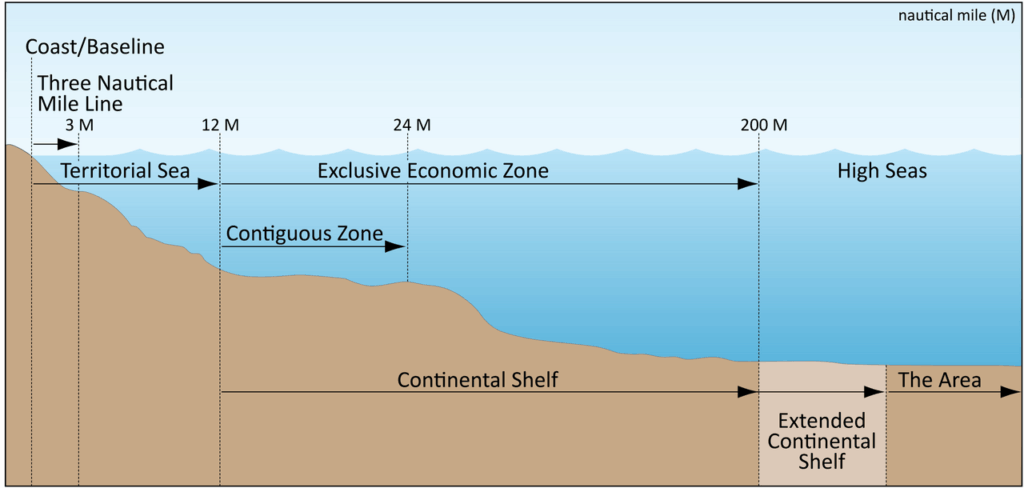

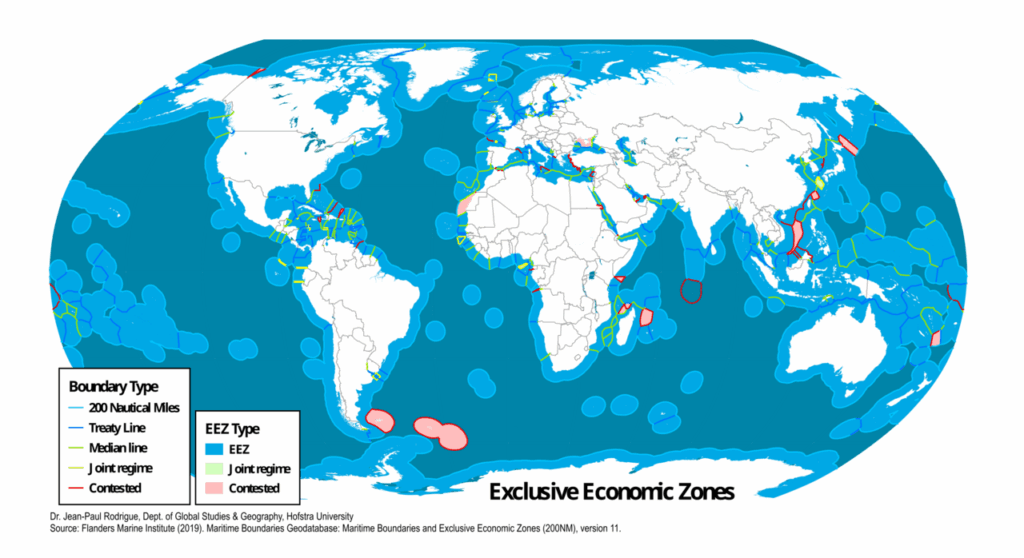

UNCLOS assigned each coastal state an exclusive economic zone extending 200 nautical miles (370.4 km) from the end of the state’s territorial waters, a strip of 12 nautical miles (12.4 km) along its coastline. For the high seas beyond national jurisdiction, UNCLOS declared that this area and its resources are the ‘common heritage of mankind,’ open to all states, whether coastal or landlocked, and that no state may subject any part of the high seas to its sovereignty.

Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue / Wikimedia)

In practice, this provisional regulation proved to be ineffective for the high seas. Therefore, in 2017, the United Nations General Assembly decided to create an international, legally binding instrument for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ). After difficult and lengthy negotiations, the BBNJ agreement was signed by 149 states and entered into force on 17 January 2026 after being ratified by 83 states, including all major fishing, shipping and mining countries with the exception of the US (not yet ratified) and Russia (not even signed) [3].

I’d like to subscribe to the think.fish newsletter.

What has (not) been achieved

As OceanCare sums it up [4], ’the High Seas Treaty (BBNJ agreement)

- improves the protection of marine biodiversity through marine protected areas and stronger environmental safeguards.

- establishes a new global framework with fair and inclusive rules for sharing benefits arising from marine genetic resources.

- is a win for multilateralism and reflects decades of work by governments, scientists, NGOs, Indigenous leaders, youth and ocean advocates.’

However, OceanCare hits the nail on the head: ’Now the crucial phase begins: only effective implementation and strong institutions can ensure lasting protection of the oceans.’

To protect marine life from surface to seabed

The problems are not only on the surface, in industrial overfishing and excessive shipping traffic, but affect all marine life down to the deepest zones, the seabed and its mineral resources, which are highly coveted. A German documentary film [5] full of astonishing images of the diverse and interconnected life underwater shows what is at stake for the oceans, and thus for life on the entire planet, if we continue to use and exploit this complex habitat unabated. The BBNJ agreement is a first step towards limiting ourselves to a sustainable level.

The reliability of international treaties is increasingly under pressure, and this also applies to the seabed. The moratorium on deep-sea mining [6], which has now been signed by 40 countries (though not the largest ones), is still being observed, but some countries, notably the United States, are pushing to explore and exploit the promising resources hidden in the depths, despite the unknown but much-feared ecological risks.

Race in the far North, not only in Greenland

Read, for example, the reportage on Svalbard (Spitsbergen), a group of small islands near the North Pole that Norway claimed as its territory after the First World War. In 1920, 14 countries agreed, on condition that Svalbard would be accessible to all without a visa for scientific and economic ventures. Forty-eight countries have now signed the treaty, including the USA, China, and Russia. Over the course of a century, a very peculiar international society with local democratic structures has developed, in which foreigners have had the right to vote since 2001. Now that the ice sheets are melting and techniques for extracting resources from the seabed have improved, Norway is attempting to strengthen its grip over the islands and their exclusive economic zone and has therefore begun to restrict immigration to and land purchases on Svalbard and to grant foreigners the right to vote on the islands only if they have lived on the Norwegian mainland for at least three years. [7]

Diet for a Small Planet

And how will big and hungry states be called to account for fishing too much, shipping too much, mining too much? What is the affordable ’Diet for a Small Planet’ (Frances Moore-Lappé, 1971), and what global force can ensure it for everyone?

References:

[2] UNCLOS

[3] BBNJ agreement

[5] ARD phoenix, 05.12.2025: ‚Der Ozean – Oase des Lebens‚

[6] Deap-Sea Mining Moratorium

[7] New York Times, 11.01.2026: ‚The Tug of War at the Top of the World‘

Schreibe einen Kommentar

Du musst angemeldet sein, um einen Kommentar abzugeben.