Der in der NZZ am 18. Januar 2025 publizierte «Leitfaden für einen nachhaltigen Fischkonsum» [1] enthält ein paar Informationen, die bewusst Konsumierende leicht in die Irre führen könnten. Ich erlaube mir daher ein paar Hinweise.

Es fängt bereits beim Titel an. Ist «Forelle statt Lachs» wirklich ratsam? Um Wildfisch kann es sich so oder so kaum handeln; wildlebende heimische Forellen sind so selten geworden wie wildlebende Atlantische Lachse. Also aus Aquakultur, und hier ist die direkte Belastung der Umwelt bei der Mast von Forellen, Ausnahmen vorbehalten, tatsächlich geringer als bei der Mast von Lachsen [2]. Aber damit die Forellen zur Schlachtreife wachsen, brauchen sie genau wie ihre grösseren Verwandten Fischmehl und Fischöl im Futter, und diese Bestandteile stammen in der Regel aus einer hierauf spezialisierten Fischerei, die mit zur Überfischung der Meere beiträgt.

Besser Wildfang als Zucht

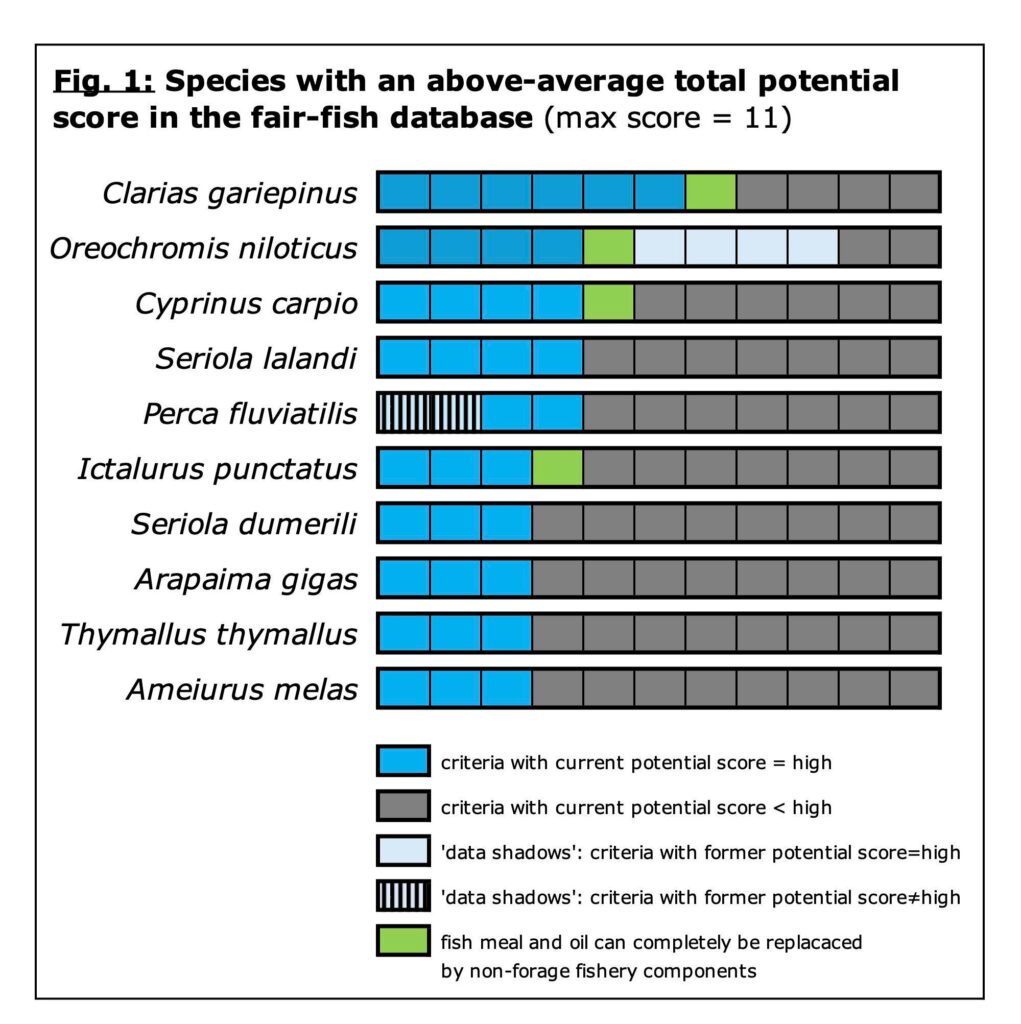

Zu recht wird die Fischzucht im Artikel als problematisch dargestellt. Sie ist es in erster Linie aus Sicht der Fische selbst, auch wenn darüber meist nicht gesprochen wird. Fast alle der heute gezüchteten Fischarten können sich in Gefangenschaft gar nicht wohl fühlen, egal mit welchem Label – sie sind von ihrer Natur schlicht nicht geeignet dafür [3]. Das hat auch Folgen für die Qualität auf dem Teller. Schon aus Egoismus am Genuss wäre es klüger, sich dafür einzusetzen, dass die Fischerei weltweit endlich nachhaltig betrieben wird – sie könnte so bis zu 60 Prozent mehr Fangertrag bringen als heute und damit Fischzucht weitgehend unnötig machen. Schonende Fangmethoden sind zudem eine wichtige Voraussetzung für eine Fischerei, die das Leiden der Tiere so gering als möglich halten soll – ein wachsendes Anliegen, das aktuelle Forschung erfüllen helfen will [4].

Rat: max. 1x Fisch im Monat

Fischlisten und Labels kranken bei wildgefangenen Fischen allerdings an der sehr ungenauen Deklaration der vielen verschiedenen Fangmethoden und an der mangelnden Detailkenntnis der Kundschaft. Das Problem liesse sich lösen durch ein strenges Label, das konsequent nur für die schonendsten Fangmethoden vergeben würde. Der Fang der im Artikel erwähnten Schollen und Flundern mit Grundschleppnetzen könnte die Bedingungen eines derartigen Labels allerdings kaum erfüllen, genau so wenig wie die Fänge mit Stellnetzen in der Schweizer Berufsfischerei.

Ein konsequentes Label solcher Art ist freilich nicht in Sicht. Bis auf weiteres ist im Einkaufsalltag eine einfache Faustregel der beste Rat: maximal eine Fischmahlzeit pro Monat [5] – das bringt auch rascher Wirkung für die Fische und ihre Umwelt.

Titelbild:

Fischgeschirr von Tremaen Pottery (Foto: Phil Holmes / Wikimedia Commons)

Quellen:

[1] https://www.pressreader.com/switzerland/neue-zurcher-zeitung-v/20250118/282364045337941

[2] Trout instead of salmon? Ask the trout!

oder hier

[3] Fish welfare in aquaculture