Gut die Hälfte des Fischs, der weltweit gegessen wird, stammt nicht von industriellen Fangschiffen, sondern aus der kleinen Fischerei. Sie könnte ohne die industrielle Konkurrenz sogar einen noch grösseren Anteil liefern.

(mehr …)

Gut die Hälfte des Fischs, der weltweit gegessen wird, stammt nicht von industriellen Fangschiffen, sondern aus der kleinen Fischerei. Sie könnte ohne die industrielle Konkurrenz sogar einen noch grösseren Anteil liefern.

(mehr …)animal suffering Animal welfare artisanal fisheries Batäubung Belt-and-Road-Initiative Blauhai Bosporus bottom trawl bycatch Canada Catch Welfare Plattform certification CFFA CAPE Chancay Chile China Containerhafen Don Staniford Erderwärmung escapes EU Europa Exclusive Economic Zone EEC fair-fish fair-fish database Faroe Fischereiabkommen Fischereisubventionen Fischmehl Fischöl fisheries agreements fisheries management FishEthoGroup fish meal fish oil Fish stocks Fish welfare Gesellschaft Greenpeace Humpback whale ICES ICSF Intelligenz International maritime law Invertebraten Kognition Korruption labels Lachs Lachszucht Litopenaeus vannamei Marine Protected Areas (MPA) migration mortality Mycroprotein Nervensystem North-east Atlantic Oceana Oktopoden Omega-3 Ostsee Pacific whiteleg shrimp Pakistan Panamakanal Parasiten Peru Philippines phytoplankton play Pole and line Polen Rainer Froese Raumfahrt Ray Hilborn Reducing animal suffering Salmon Sandtigerhai Schifffahrt Schottland sea lice Seawater Cube Senegal Slapp small-scale fisheries small scale fisheries stocking density Tierleid Tierschutz Tintenfische UK US Navy Venezuela Westafrika whales Whale shark Wirbellose WTO Zivilisation Zooplankton Überfischung

#1: Fish farming on ships

Due to the continued growth of aquaculture, the available space for new breeding sites is becoming scarce, both on land and along the coast. A Chinese company has just converted an old cargo ship into a floating fish farm and is promoting this as a more cost-effective alternative to land-based salmon farming [1]. European fishing companies are also planning to use ships for fish farming in order to circumvent delays in the approval of offshore sites and in view of China’s progress [2]. However, it is questionable whether fish farming on ships far away from the public eye is more sustainable and, above all, more respectful towards animals

(mehr …)animal suffering Animal welfare artisanal fisheries Batäubung Belt-and-Road-Initiative Blauhai Bosporus bottom trawl bycatch Canada Catch Welfare Plattform certification CFFA CAPE Chancay Chile China Containerhafen Don Staniford Erderwärmung escapes EU Europa Exclusive Economic Zone EEC fair-fish fair-fish database Faroe Fischereiabkommen Fischereisubventionen Fischmehl Fischöl fisheries agreements fisheries management FishEthoGroup fish meal fish oil Fish stocks Fish welfare Gesellschaft Greenpeace Humpback whale ICES ICSF Intelligenz International maritime law Invertebraten Kognition Korruption labels Lachs Lachszucht Litopenaeus vannamei Marine Protected Areas (MPA) migration mortality Mycroprotein Nervensystem North-east Atlantic Oceana Oktopoden Omega-3 Ostsee Pacific whiteleg shrimp Pakistan Panamakanal Parasiten Peru Philippines phytoplankton play Pole and line Polen Rainer Froese Raumfahrt Ray Hilborn Reducing animal suffering Salmon Sandtigerhai Schifffahrt Schottland sea lice Seawater Cube Senegal Slapp small-scale fisheries small scale fisheries stocking density Tierleid Tierschutz Tintenfische UK US Navy Venezuela Westafrika whales Whale shark Wirbellose WTO Zivilisation Zooplankton Überfischung

Wenn europäische und asiatische Industrieschiffe die Küsten Westafrikas leerfischen, werden einheimische Fischerboote zu Fluchtbooten für die gefährliche Überfahrt nach den Kanarischen Inseln, die zu Spanien gehören. Wieder einmal ist kürzlich eines dieser nicht für die hohe See gebauten Boote gekentert, vermutlich gegen hundert Menschen sind vor der Küste Mauretaniens ertrunken [1]. Die angeblich partnerschaftlichen Fischereiabkommen zwischen der EU und den westafrikanischen Staaten ändern nichts an den Fluchtgründen.

(mehr …)animal suffering Animal welfare artisanal fisheries Batäubung Belt-and-Road-Initiative Blauhai Bosporus bottom trawl bycatch Canada Catch Welfare Plattform certification CFFA CAPE Chancay Chile China Containerhafen Don Staniford Erderwärmung escapes EU Europa Exclusive Economic Zone EEC fair-fish fair-fish database Faroe Fischereiabkommen Fischereisubventionen Fischmehl Fischöl fisheries agreements fisheries management FishEthoGroup fish meal fish oil Fish stocks Fish welfare Gesellschaft Greenpeace Humpback whale ICES ICSF Intelligenz International maritime law Invertebraten Kognition Korruption labels Lachs Lachszucht Litopenaeus vannamei Marine Protected Areas (MPA) migration mortality Mycroprotein Nervensystem North-east Atlantic Oceana Oktopoden Omega-3 Ostsee Pacific whiteleg shrimp Pakistan Panamakanal Parasiten Peru Philippines phytoplankton play Pole and line Polen Rainer Froese Raumfahrt Ray Hilborn Reducing animal suffering Salmon Sandtigerhai Schifffahrt Schottland sea lice Seawater Cube Senegal Slapp small-scale fisheries small scale fisheries stocking density Tierleid Tierschutz Tintenfische UK US Navy Venezuela Westafrika whales Whale shark Wirbellose WTO Zivilisation Zooplankton Überfischung

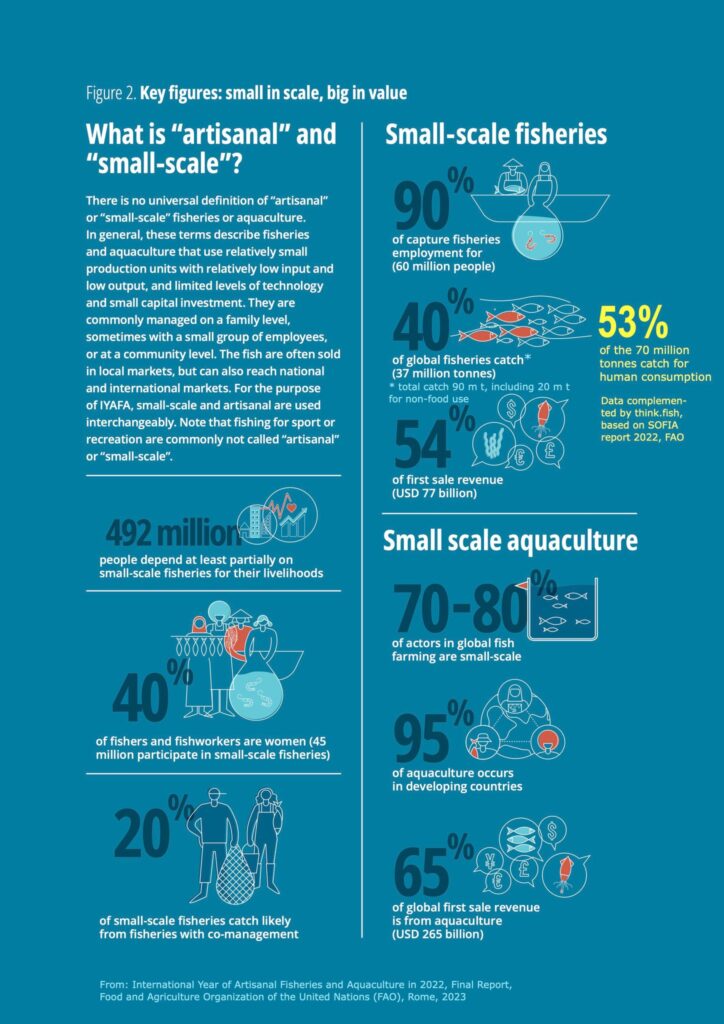

Small-scale artisanal fisheries are largely underestimated in terms of their catch volumes and contribution to the local economy — and at the same time they are adversely affected by industrial fishing, offshore aquaculture, tourism and other uses of coastal waters. Assessing the value and importance of small-scale fisheries is a crucial step towards countering the threats they face. This also benefits fishes, because if fisheries can minimise the suffering of the animals concerned, small-scale fisheries are more likely to succeed than their industrial competitors, which use heavy fishing gear.

(mehr …)animal suffering Animal welfare artisanal fisheries Batäubung Belt-and-Road-Initiative Blauhai Bosporus bottom trawl bycatch Canada Catch Welfare Plattform certification CFFA CAPE Chancay Chile China Containerhafen Don Staniford Erderwärmung escapes EU Europa Exclusive Economic Zone EEC fair-fish fair-fish database Faroe Fischereiabkommen Fischereisubventionen Fischmehl Fischöl fisheries agreements fisheries management FishEthoGroup fish meal fish oil Fish stocks Fish welfare Gesellschaft Greenpeace Humpback whale ICES ICSF Intelligenz International maritime law Invertebraten Kognition Korruption labels Lachs Lachszucht Litopenaeus vannamei Marine Protected Areas (MPA) migration mortality Mycroprotein Nervensystem North-east Atlantic Oceana Oktopoden Omega-3 Ostsee Pacific whiteleg shrimp Pakistan Panamakanal Parasiten Peru Philippines phytoplankton play Pole and line Polen Rainer Froese Raumfahrt Ray Hilborn Reducing animal suffering Salmon Sandtigerhai Schifffahrt Schottland sea lice Seawater Cube Senegal Slapp small-scale fisheries small scale fisheries stocking density Tierleid Tierschutz Tintenfische UK US Navy Venezuela Westafrika whales Whale shark Wirbellose WTO Zivilisation Zooplankton Überfischung

Small-scale artisanal fisheries are largely underestimated in terms of their catch volumes and contribution to the local economy — and at the same time they are adversely affected by industrial fishing, offshore aquaculture, tourism and other uses of coastal waters. Assessing the value and importance of small-scale fisheries is a crucial step towards countering the threats they face. This also benefits fishes, because if fisheries can minimise the suffering of the animals concerned, small-scale fisheries are more likely to succeed than their industrial competitors, which use heavy fishing gear.

(mehr …)animal suffering Animal welfare artisanal fisheries Batäubung Belt-and-Road-Initiative Blauhai Bosporus bottom trawl bycatch Canada Catch Welfare Plattform certification CFFA CAPE Chancay Chile China Containerhafen Don Staniford Erderwärmung escapes EU Europa Exclusive Economic Zone EEC fair-fish fair-fish database Faroe Fischereiabkommen Fischereisubventionen Fischmehl Fischöl fisheries agreements fisheries management FishEthoGroup fish meal fish oil Fish stocks Fish welfare Gesellschaft Greenpeace Humpback whale ICES ICSF Intelligenz International maritime law Invertebraten Kognition Korruption labels Lachs Lachszucht Litopenaeus vannamei Marine Protected Areas (MPA) migration mortality Mycroprotein Nervensystem North-east Atlantic Oceana Oktopoden Omega-3 Ostsee Pacific whiteleg shrimp Pakistan Panamakanal Parasiten Peru Philippines phytoplankton play Pole and line Polen Rainer Froese Raumfahrt Ray Hilborn Reducing animal suffering Salmon Sandtigerhai Schifffahrt Schottland sea lice Seawater Cube Senegal Slapp small-scale fisheries small scale fisheries stocking density Tierleid Tierschutz Tintenfische UK US Navy Venezuela Westafrika whales Whale shark Wirbellose WTO Zivilisation Zooplankton Überfischung

Artisanal fisheries provide 53% of the fish consumed worldwide, 90% of employment in fisheries, predominantly in the Global South, and 54% of all catch sale revenues (see graph below). They could provide even more if they were not harried by industrial fisheries. Instead, artisanal fisheries are disregarded.

Artisanal fisher(wo)men in the Global South complain about the frequent disregard of their human rights and demand that their traditional rights to access to water bodies, fishing grounds, landing and transformation sites, and to the market be recognised.

Fisherwomen in particular complain of discrimination and call for their crucial role in artisanal fisheries, families, and communities to be recognised.

Fishing communities complain of marginalisation and demand access to public infrastructure, social services, and development.

On top of these problems, artisanal fisheries on the shores of seas and lakes are among the first to be affected by global warming and therefore need support to overcome its negative impacts.

This is a short summary of workshops with artisanal fisher(wo)man held during the International Year of Artisanal Fisheries and Aquaculture in 2022, made available through a worth seeing video recently by ICSF [1].

The personal summary of one of the ICSF workshop participants is especially interesting:

‚Maybe we have to look where we haven’t looked before, put ourselves in the skin of the fish.‚

Good point! Putting yourself in the skin of a fish — whether as a consumer, chef,retailer, fishmonger or a primary producer — would also mean to recognise also the rights of the fishes to be at least treated with respect and spared harm as much as possible. It is understandable that fishermen who struggle for their own survival do not pay much attention to the struggle of the animals. A key to substantially reducing animal suffering in fisheries is to improve the living conditions of artisanal fisher communities. The still unrivalled project of fair-fish and artisanal fisheries in Senegal in the noughties [2], which failed because the market was not ready yet, is still waiting for imitators.

Title picture:

Artisanal fishermen on the Saloum, Senegal (credit: Michael Hauri)

Sources:

[1] Video about the ICSF Workshops in the International Year of Artisanal Fisheries and Aquaculture (IYAFA, 2024). Thanks to the International Collective in Support of Fishworkers (ICSF) that organised the workshops reported by this video,

[2] see the in-depth chapter in the fair-fish book about the project in Senegal

animal suffering Animal welfare artisanal fisheries Batäubung Belt-and-Road-Initiative Blauhai Bosporus bottom trawl bycatch Canada Catch Welfare Plattform certification CFFA CAPE Chancay Chile China Containerhafen Don Staniford Erderwärmung escapes EU Europa Exclusive Economic Zone EEC fair-fish fair-fish database Faroe Fischereiabkommen Fischereisubventionen Fischmehl Fischöl fisheries agreements fisheries management FishEthoGroup fish meal fish oil Fish stocks Fish welfare Gesellschaft Greenpeace Humpback whale ICES ICSF Intelligenz International maritime law Invertebraten Kognition Korruption labels Lachs Lachszucht Litopenaeus vannamei Marine Protected Areas (MPA) migration mortality Mycroprotein Nervensystem North-east Atlantic Oceana Oktopoden Omega-3 Ostsee Pacific whiteleg shrimp Pakistan Panamakanal Parasiten Peru Philippines phytoplankton play Pole and line Polen Rainer Froese Raumfahrt Ray Hilborn Reducing animal suffering Salmon Sandtigerhai Schifffahrt Schottland sea lice Seawater Cube Senegal Slapp small-scale fisheries small scale fisheries stocking density Tierleid Tierschutz Tintenfische UK US Navy Venezuela Westafrika whales Whale shark Wirbellose WTO Zivilisation Zooplankton Überfischung